Forty light years away, seven Earth sized planets orbit around a dim red dwarf star in one of the most tightly packed planetary systems ever discovered. The TRAPPIST-1 system has captivated astronomers since 2017, with three of its planets orbiting in the habitable zone where liquid water might exist. But there’s been a lingering question whether any of these worlds could hold onto moons?

New research by Shubham Dey and Sean Raymond suggests the answer is yes, though the moons would need to stay close to their host planets and couldn’t be particularly large.

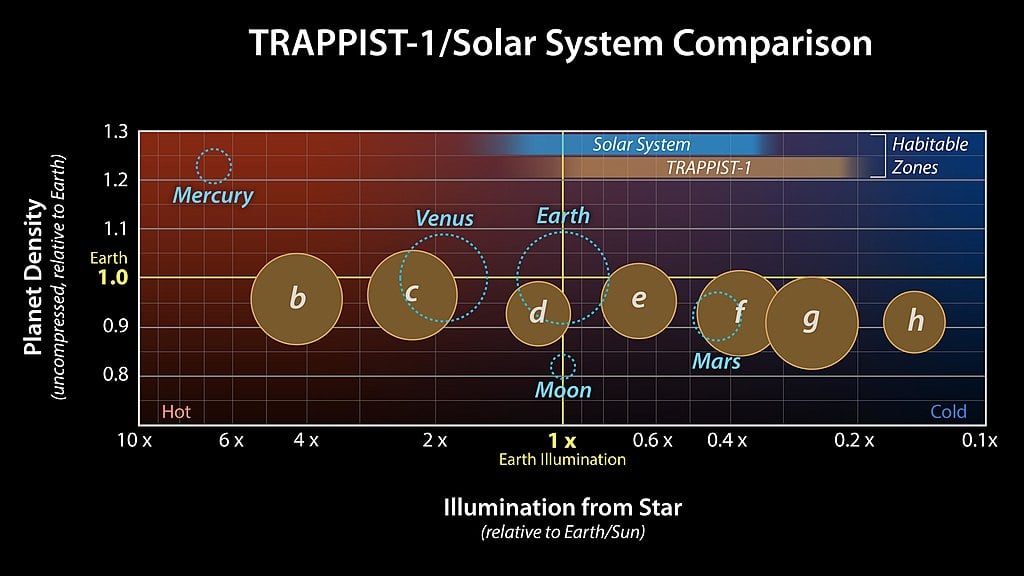

Relative sizes, densities and illumination of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system compared to the inner planets of the Solar System (Credit - NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Relative sizes, densities and illumination of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system compared to the inner planets of the Solar System (Credit - NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The team ran thousands of computer simulations testing how theoretical moons would fare around each TRAPPIST-1 planet. They started by placing 100 virtual moons in circular orbits around each world, spacing them from the Roche limit where a moon would be torn apart by tidal forces.

First, they tested each planet in isolation. The results showed moons could remain stable in a zone extending from the Roche limit out to roughly half the Hill radius, matching theoretical predictions. But TRAPPIST-1’s seven planets don’t exist in isolation. They orbit in a resonant chain, like a gravitational clockwork mechanism, constantly tugging on one another.

When the simulations included neighbouring planets, things changed. The gravitational interference from companions squeezed the stable zone inward, particularly for TRAPPIST-1 b (the innermost planet) and TRAPPIST-1 e (which sits in the habitable zone). The outer stability boundary contracted to about 40-45% of the Hill radius for each world when all seven planets were present.

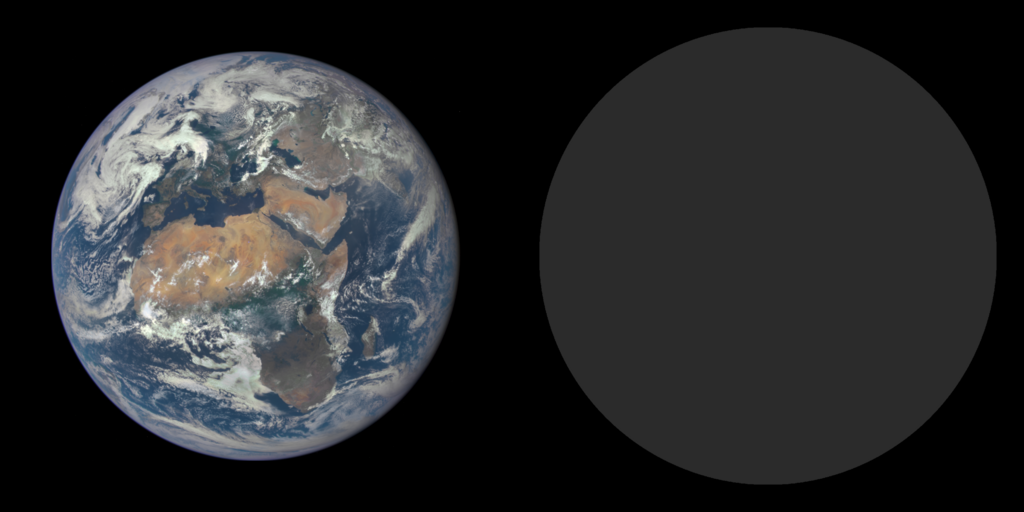

*Illustration comparing Earth and TRAPPIST-1 b*

*Illustration comparing Earth and TRAPPIST-1 b*

The contraction isn’t dramatic though with individual neighbouring planets producing weak effects on their own but the combined gravitational influence of the full system creates a resonant squeeze. Still, there’s plenty of room for moons to survive if they stay close enough to their host planet.

The researchers calculated that tidal forces would cause larger moons to gradually spiral inward and crash into their planets over billions of years. Only moons smaller than about one ten millionth of Earth’s mass could survive these forces throughout TRAPPIST-1’s lifetime, with the outer planets potentially hosting slightly more massive satellites.

Whether such moons actually exist is another question entirely. Detection remains beyond current capabilities. But the research establishes that TRAPPIST-1’s compact, resonant architecture doesn’t preclude moons it just demands they stay small and close to home.

Source : Orbital Stability of Moons Around the TRAPPIST-1 Planets

Universe Today

Universe Today